Something struck me as peculiar in Friday's Armstrong and Getty radio program. It was in hour two, on “Geeks and Playgrounds.”

They covered this story from Reason: German Insurance Companies Demand Perilous Playgrounds So That Kids Can Learn About Risk.

My first question was, who is calling for this? Health insurers or property and casualty insurers, or both?

Turns out it is not the traditional health insurance market, but accident insurers. I think of accident insurers as more closely aligned with property and casualty since they pay you for harm done after the fact instead of covering medical costs as you go. But it doesn’t matter for this analysis; I just found that interesting.

The Reason article states:

With young people

spending an increasing amount of time in their own home, the umbrella

association of statutory accident insurers in Germany last year called

for more playgrounds that teach children to develop 'risk competence.’

Insurance lets you purchase a piece of mind for risks that make you uncomfortable. Ideally, it is for risks you know you cannot cover alone. Of course, it is also used for risks that would be too painful to cover, such as if it required you to sell your home or your fist born. I always start there. Most white-collar folks who make more than $100K annually should buy the highest deductible they can stomach for home and auto insurance.

Furthermore, unless an employer pays for all or most of it, there is no need for dental or vision insurance. Those are risks we can assess and should have enough savings to cover. Paying an insurer to do so inserts a middleman, pays them a profit and leaves you worse off.

What do we need? Medical and disability insurance. We also may need life insurance if we have dependents. Eventually, you should get to a point in life where you no longer need it. I.e., kids out of college, home paid off, some savings in the bank. At that point, your dependents will be fine with your assets.

My second question was: why do German accident, property, and casualty insurers want Germans to be better with risk? My initial instinct tells me that this was against their interests. Snowflakes who grow up cringe harder and fear more. Thus, they will buy more insurance, even if it is irrational. And that generates larger profits for insurers. But then I realized I was likely thinking too long-term. Publicly traded corporations may talk in terms of three to five-year plans, but in reality, they had better show growth this quarter lest they want to get a public spanking.

The article does go on to state, "children who had improved their motor skills in playgrounds at an early age were less likely to suffer accidents as they got older." That does lead one to believe that this is about profitability. But I still don't fully buy it. Why? Because as soon as they begin to see more accidents due to a wincing, flaccid populace, they can justify higher premiums and make more profit.

Granted, property and casualty insurers use different loss ratios than health insurers, but the following analogy illuminates the point. In America, it is widely accepted that insurers can make a modest and reasonable profit at an 87% loss ratio. That means the insurer pays 87 cents in claims for every dollar collected in premium, leaving 13 cents on the dollar to pay salespeople, train staff, hire administrative folks, pay rent, and pay taxes.

Obamacare's Perverse Unintended Consequence

Back to Deutschland

What is really going on in Germany? I’m not entirely sure. If I take my tinfoil hat off and make an effort to be altruistic (just for a minute, Ayn. It’s just a thought experiment!) I might conclude that the German insurers are genuinely doing what they think is best for their nation. I mean, it is still possible for mega-corps to do the right thing for the right thing’s sake, isn’t it?

Just kidding. It is likely something a little deeper. Actuarial tables are complex sets of data tasking actuaries and, eventually, underwriters with the “art” of assessing risk. Yeah, it is more of an art than a science, as much as they want you to believe it is perfectly cold and calculated. Don’t get me wrong. Their job is, as my buddy Gary would say, “harder than a whore’s heart.” But there is so much wiggle room in there that if policyholders knew how the sausage was made, they’d likely go vegan. And don’t think for a minute government actuaries do any better. For example, when Medicare and Medicaid first passed in 1965, government bean counters told us it would cost $12 billion by 1990. In reality, it was $110 billion.

More recently, Obamacare originally had long-term care insurance embedded within. But the reality on that line of coverage is that folks are living so much longer now, in old folks’ homes and in need of continual care, that the industry still has not come up with a reliable way to assess this risk. Hence, congress repealed Obamacare’s LTC program before it ever got off the ground. Californitopia also recently eliminated its LTC coverage in CalPERS.

The point is, as much as I want to believe insurers can simply raise premiums to cover increased risk, it’s not something that easily happens overnight. And the one thing that insurers hate more than anything is … the unknown. If they can’t measure and assess it, they pull the product or jack the rates so high that nobody wants to buy. Obamacare cemented that trick for American health insurers:

Sure, you can keep it so long as you can afford the premium increases, your employer doesn’t change carriers, and your carrier continues to offer the same obsolete plan even though they are now required, in every state, to license a whole new litany of plans that comply with Obamacare’s mandated bloat. Easy peasy.

The Patient Disruption and Unaffordable Care Act made a rule that mandated insurers always renew coverage at year’s end. Pre-2010, your insurer could cancel you if you had an epically bad year. Obamacare fixed that. Now, carriers issue 75% renewal increases to accomplish the same thing. Problem solved.

Conclusion(s)

I’m left with three possible conclusions as I ponder this story:

1. (1) If German

accident insurers operated under the same warped, public-private partnership (i.e.,

fascistic)

rules as Obamacare, not only would those insurers display indifference toward greater

childhood risk-ignorance, they would foster it. That would lead to more claims and be the only

way German insurers could generate more revenue in the future. Again, 15% of a billion is much better than 15%

of a million. Aren’t price controls

neat?

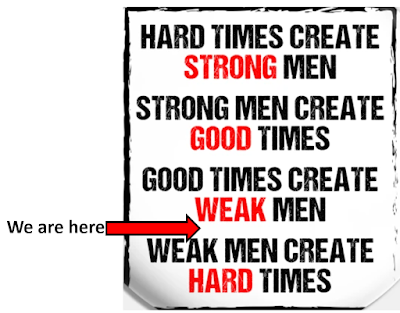

2. (2) Enough cynicism. Let me white pill this for a moment. It is certainly possible that the insurers want what is best for Germany. And, as they look across the pond to their WWII liberators, they see what happens when you fastidiously bubble-wrap your youth in endless layers of protection. It’s not good. Good times are definitely creating weak men. So, at least on its face, there is an argument that the Deutschlanders are solely doing what is right for their youth.

3. (3) This brings me to my third and most likely conclusion. Germany’s carriers are horrified at the speed at which the namby-pamby are changing risk calculus. Hence, Germany’s plea to allow more risk and play on more dangerous playgrounds is more likely tied to the bottom line. It is not our Obamacare analogy or altruism; instead, it is most like our U.S. long-term care calculus. In their eyes, if people become more paranoid and want to buy more coverage for perceived risks, great. But let’s not do this overnight because we still must have some clue as to how to underwrite our precious little snowflakes in the short term. For a carrier, claim expansion is great for business over the long haul if it is predictable and can be ushered in with higher premiums. But the market will topple when the claims skyrocket in a short enough period (like 1 to 3 years).

Alas, this third conclusion is actually

the scariest. Accident insurers (at

least in Germany) are signaling that the wussification of our youth is

happening so fast, they are not confident in their ability to profit from

it. It’s bad enough that we

bubble-wrapped our snowflakes as we hover over them in helicopters to ensure

nothing bad ever happens. But we’re doing

it so fast that the oligarchs and the oligopoly are worried that our degradation

will infringe upon their ability to plunder from our demise.